What is NIL, and how did we get here?

Defining NIL

NIL (Name/Image/Likeness) is shorthand for a student-athlete’s intellectual property rights (their name, image, and likeness).

A Brief History of How We Got Here

It is important to put the current conversation about NIL reform in context. The NCAA was founded after a White House meeting in which Teddy Roosevelt met Ivy League football coaches and administrators to push them into adopting rules to make football safer. (There had been a rash of student deaths and injuries playing the unregulated new game.) The newly minted organization, which became the NCAA in 1910, was founded on three major principles: mandatory football helmets, adopting Harvard’s rules rather than Yale’s (including the invention of the forward pass), and a strict ban on recruiting or offering any financial compensation to student-athletes. It is important to note the NCAA did not develop enforcement mechanisms until the 1950s. These enforcement mechanisms were adopted alongside the recognition that schools COULD provide “athletically related financial aid” known as athletic scholarships.

Fast forward to 2009 when a former UCLA basketball player, Ed O’Bannon, sued the NCAA (along with EA Sports and the Collegiate Licensing Company) for using his likeness in a video game without credit or permission. It was clear that the NCAA’s legal position in this case was exceptionally weak and that continuing to monetize student-athlete’s intellectual property without compensation was becoming untenable. In fact, EA Sports and CLC settled the lawsuit and paid out $40 million to be distributed to the student-athletes whose likenesses had been used without permission, but the NCAA took the case to trial and lost; this established a legal precedent that it could not monetize student-athlete’s intellectual property without consent, providing a roadmap for more class action lawsuits based on antitrust law. The NCAA has lost several subsequent challenges and is currently enjoined from enforcing bylaws limiting NIL payments and on transfer limitations.

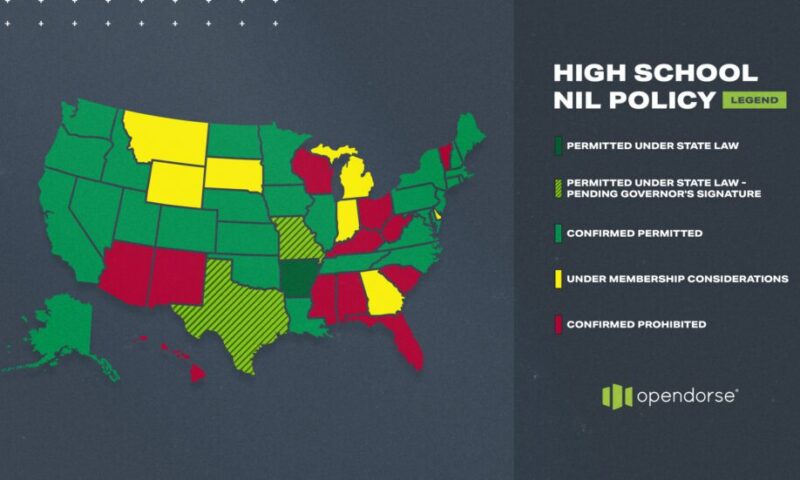

NIL reform has also been adopted by individual states. Many states passed legislation to mandate students at the college (and in many states the high school level) be able to freely profit from their intellectual property (see Figures 1 and 2).

The State of Play Today

What has developed is a three-tiered NIL system. The top tier impacts students who develop significant commercial value and can monetize that value individually.

The most broadly influential tier on the college side is made up of NIL “collectives.” These collectives are independent entities that come together to support athletics at a specific college. They offer prospective students compensation as an inducement to attend and/or to remain at the school and are responsible for the majority of NIL value right now.

There is also a low-value/exploitative tier of NIL. This tier includes companies that purchase intellectual property for minimal payments, barter, or just the promise of possible payment. Their business model involves small-scale investment, inducing students to give up their intellectual property without understanding its value.

Advising Students

In this environment, it is very important for students who DO monetize their NIL rights in high school to make sure their contracts sunset prior to their enrollment in college so they have maximum ability to negotiate with the college collectives. Once the collective deal (and athletic scholarship) is secured, THEN the student can monetize their rights with additional deals. It is also critical to have all contracts reviewed by a competent and knowledgeable intellectual property attorney. Most schools with significant NIL collectives can make these experts available to their students at minimal/no cost.

For students who are NOT looking at NIL deals based on their athletic profile or social media influence, there is a significant space for entrepreneurship and creativity to build value. Advisors should be encouraging students to explore this space even for athletes who are not attracting elite offers!

I believe that IECs should advocate for colleges to support and enhance the value of their student’s intellectual property. This would push more students into top-tier business agreements and generate more value for everyone. It is critical that colleges develop workable rules for the second tier “collectives.” An unregulated arms race is inevitably going to exploit some students; making sure that the benefits are spread more widely and in a way that is congruent with the college’s educational mission is broadly good policy that could gain support across stakeholders. Finally, it is in everyone’s interest to protect student-athletes from exploitation by the lowest tier of actors in the NIL space. All these issues require legislative action and lobbying at both the state and federal levels. While I personally feel this is the right approach, there is no shortage of opinions about the best path forward.

Policy Possibilities

The current patchwork of state laws, temporary restraining orders, and legal opinions makes action via the NCAA legislative process problematic. Coming to grips with this new legal and commercial landscape will require all the stakeholders involved in intercollegiate athletics to collaborate in developing a new framework that can be adopted as federal legislation and executive branch regulation. From the NCAA’s perspective, the best-case scenario is legislation that provides the NCAA an exemption from antitrust law. But it could also mean federal legislation setting a framework for the compensation of student-athletes and/or empowering the NCAA to enforce member adopted legislation within certain defined parameters. NCAA member schools and executive leadership, especially among the College Football Playoff schools has an outsized influence to set the tone of this debate and needs to engage with this process in a strategic way with a unified agenda. This agenda has not been communicated either by college presidents or the NCAA executive staff, and we have not seen a clear process involving all stakeholders yet outlined.

In the absence of clear leadership from the NCAA, we have a variety of efforts at influencing policy coming from different actors. There is a highly publicized effort to unionize student-athletes with the idea that the NCAA would come to a collective bargaining agreement with some kind of NCAA Players Association. But this approach has several serious problems, including serial failure in court. Just this week, a highly publicized effort to re-classify student-athletes at Dartmouth as “employees” featuring the Dartmouth basketball team was challenged by the university and is currently under review by the NLRB. There are also a variety of lobbying efforts at the state level, but no state action solves the problem of a national organization needing national policy to provide clarity to its members.

Dave Morris, MEd, IECA (WA), College Athletic Advisor, can be reached at [email protected].

This information is so helpful! Thank you, Dave!