If you are working with students applying to graduate school in clinical psychology—or planning to do so in the future—you are bound to confront the question: what is the difference between a PhD in clinical psychology and a PsyD program?

How do these two degrees vary in terms of application requirements, academic experience, and career paths offered?

Furthermore, what can psychology students who graduate with a master’s degree go on to do? I have worked with applicants to graduate programs in psychology for over ten years and recently spoke with four knowledgeable professionals to gain an even deeper understanding of the options available to students. In the article below, I’ll walk you through defining features of the various graduate degrees in psychology and discuss how to help your students make the best choice for their interests, preferences, and goals.

Overview of Accredited Program Types

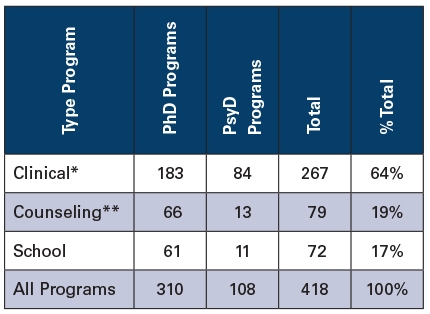

First, let’s take a look at the options students have, by the numbers. There are 418 APA-accredited doctoral programs of psychology, including 310 PhD programs and 108 PsyD programs, according to the American Psychological Association. The chart below shows the number of PhD and PsyD programs in the US and Canada, and the types of accredited programs.

* Clinical programs include five PhD programs that combine clinical with counseling or school and seven PsyD programs

* Clinical programs include five PhD programs that combine clinical with counseling or school and seven PsyD programs

** Counseling programs include three PhD programs that combine counseling with school and one PsyD program

Interestingly, very few universities offer both PhD and PsyD programs, and the schools that offer PhD programs tend to be the more research-based “R-1” universities (as classified by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education based on the schools’ investment and productivity in research).

PhD

The Doctor of Philosophy, or PhD, in clinical psychology is the most research-focused of the three degrees. Such programs are said to follow a “scientist-practitioner” or “scholar-practitioner” model, in which the generation of new knowledge is the first priority. PhD programs thus focus on admitting students who have at least two years of research experience prior to applying and make the creation of original scholarship a centerpiece of the graduate school experience. Such programs take five to eight years to complete, and generally require that students write a dissertation.

PhD programs tend to be small and are highly selective in their admissions. Nova Southeastern University’s PhD program, for example, admits many fewer applicants than their PsyD program because PhD students work with specific faculty members throughout their training. “We have these wonderful one-to-one number of faculty who are available to be a mentor for that applicant,” says Gregory Gayle, EdS PhD candidate in educational leadership, director of recruitment and admissions for the College of Psychology at Nova Southeastern. An added bonus of PhD programs is that they often provide students with full or partial funding.

Applying to a PhD program at which you’ll work with a specific research adviser throughout your training is “a bit of a risk if you are not completely sure what you want to study,” says Mary Thorn,* a third-year PhD student in clinical psychology at the City College of New York. But such programs tend to provide full funding, so “financially, it makes a lot of sense—but those programs are by far the most competitive, because you get a full ride.” When Thorn applied to graduate school in 2019, she looked at the faculty accepting students at each program she was considering and, if there wasn’t someone whose specific research area appealed to her, didn’t apply to that school.

Thorn applied to a total of around 15-18 graduate programs, including about two-thirds PhD programs and one-third PsyD programs—so she hadn’t decided which route to take by the time she applied. But, per her interests and background, she favored programs with a more clinical bent that were still PhD programs, which were more affordable, skewed older (Thorn was in her late twenties when she applied), and tended to have more diverse student bodies, as far as she could tell. Thorn ultimately was accepted to six PhD programs and four PsyD programs, and narrowed her choices down to three PhD programs that had more psychodynamic or mindfulness-oriented offerings than the others: Adelphi, Hofstra, and City College, which she ended up selecting.

PhD degrees are ideal for students who enjoy conducting original research, are up for a long schooling experience, want or need to spend little to no money on graduate school, and hope to pursue a combination of research, teaching, and clinical work. Many of Thorn’s classmates hope to balance out private practice with work that’s more affordable for patients and have a wide variety of career aspirations: one wants to focus on eldercare; another wants to be a sports psychologist for a premier-league team; others are particularly interested in cross-cultural studies (since research to date has primarily focused on societies that are “WEIRD”: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic). Many PhD students go on to complete post-doctoral degrees upon graduation—for example, at psychoanalytic institutes like IPTAR or the William Alanson White Institute.

“PhD—there’s more gravitas to it, and people in a social psych lens will respect it more,” Thorn says. Teaching opportunities can come more easily to PhDs, who can teach at any level, including at PhD programs. But as we’ll see in the next section, the difference between PhD and PsyD programs has become less and less acute over time.

PsyD

The Doctor of Psychology, or PsyD, is more focused on the clinical experience than the PhD. While PhDs follow a “scholar-practitioner” model, PsyDs tend to follow an inversion of it, namely: the “practitioner-scholar” model. While PhD programs train students to generate original knowledge, PsyD programs have traditionally been centered on applying said knowledge in the field. PsyD programs are a bit shorter than PhD programs—they take four to six years to complete—and do not tend to be funded.

“Historically, when PsyDs were newer to the space of psychology, the career paths were very different,” says Katherine Marshall Woods, PsyD, assistant professor of clinical psychology, director of clinical training, and deputy director of the Professional Psychology Program at George Washington University. “That is no longer the case. Most things that one can do with a PhD, one can do with a PsyD. There is no longer that sort of discrepancy.” Gayle echoes this sentiment: PhD graduates working in the academy and PsyD graduates working in the clinic “is really not a strong difference anymore,” he says. “We have individuals who are PsyDs teaching, we have individuals who have their PhD working in agencies, etcetera. But historically, that has been the difference.” Thorn points out that many PsyD programs have developed robust clinical research tracks that align to some degree with PhD programs’ research sequences. And PsyD students can, like PhD students, go on to teach at the college level, do original research, and/or become licensed psychologists (pending passing a licensing exam after graduation).

Overall, though, research requirements tend to be less rigorous in PsyD programs, whose students dive into clinical work more quickly. “In a PsyD program, it is more about applying the theory to patients within actual clinical experiences,” says Woods. PsyD students must do some research in order to graduate and can lean into it more deeply if they choose—but they usually don’t have to write a dissertation, as PhD students do. At some PsyD programs, students have a different sort of writing requirement: at GW, for example, PsyD students must compose a long piece describing a clinical experience that they’ve had with a patient. Such a work is challenging, like a dissertation, but differently focused. Other PsyD programs, like Nova Southeastern’s, do not require that PsyD students complete a capstone piece of writing at all.

Claire Beltran,* a second-year student in the PsyD program at Nova Southeastern, only applied to PsyD programs because “my main focus was to continue developing my clinical knowledge skills,” she says. “I did my undergraduate program in Bogota, Colombia and did a specialization and internship with adolescents and adults conducting evidence-based therapy. This motivated me to continue further in my career and apply to a more practice-focused degree.”

When Woods applied to graduate programs in clinical psychology, she, like Thorn, focused more on specific programs than on the PhD-versus-PsyD divide. “I was interested in this program in particular, the George Washington University PsyD program, for years—actually, since its inception, which was not that long before I went to grad school,” she says. She points to a number of unique features of the program, chief among them its psychodynamic orientation and special interest in psychoanalysis. (GW students still can take courses that follow other models, like CBT, or gain exposure to such lenses through externships.)

She was also drawn to the GW PsyD program’s focus on both the scholar and the practitioner elements of education. “You are a scholar—you are always someone who is learning—and you are an individual who practices psychology daily,” she says. At that time, she was not as interested in research: “I wanted to be somebody who was always learning and thinking and doing so while being a practitioner, and having whatever I’m learning be something that was applicable to serve the public.” PsyD students at GW typically take three years of full-time coursework in clinical psychology, followed by a yearlong internship.

Woods went on to graduate from GW’s PsyD program, and now serves on the program’s faculty. Her role involves not only teaching but also supervising students, advising, and helping students obtain training in the community as well as internships. She wears many other hats, too: she spends 12-15 hours per week treating patients in private practice; hosts a television show, A Healthy Mind, that aims to enhance community health awareness; assists filmmakers in developing characters in a way that is realistic and accurate; writes blog posts and books; and more. Her PsyD degree has enabled her to do clinical work, teach, and beyond.

Master’s

If the difference between the PhD and PsyD degree has narrowed in recent years, the master’s in clinical psychology degree still stands apart: it usually does not enable graduates to teach at the college level or practice as a licensed clinical psychologist. This makes sense, as the MA degree takes only one to two years to complete, does not involve original research, and typically involves fewer than twenty hours of fieldwork. Master’s programs, like PsyD programs, are not funded.

However, an MA in clinical psychology may be an ideal option for students who want to apply to PhD programs but don’t yet have the requisite two-plus years of research experience. It can take much longer than two years to actually amass this experience, as getting such posts can be competitive: it might take years for a student to get their first research gig. Obtaining an MA would supplant the need for such experience prior to applying.

Master’s degrees in other psychology-related fields can offer other opportunities, so such a degree might be ideal for students who are interested in psychology but don’t want to invest in upwards of four years of graduate education. Obtaining an MS in counseling, for example, enables students to work in such environments as mental health clinics, schools, hospitals, and more. Obtaining a master’s in social work, or MSW, degree, followed by many hours of supervised training as well as licensure, enables graduates to serve as clinical social workers—which can be the jumping-off point for careers as disparate as social worker on the one hand or psychoanalyst in private practice on the other.

Tips for Students

Consider Overall Career Priorities. Since there is increasing overlap between PhD and PsyD programs, I advise helping students identify, as specifically as possible, the areas they’re interested in before they apply to psychology graduate school. Start by discussing the balance they desire, for their future career, between clinical work, research, and teaching; then, drill down into the specifics of their interests. Are there subject areas, populations, and/or disorders that they feel most compelled toward?

Identify Specialty Areas. There is a wide range of specialties students can pursue, from those involving the individual and relationships (like developmental psychology, or marriage and family psychology) to school-related areas (like educational psychology or educational testing) to a variety of additional areas (like public policy, substance abuse, industrial-organizational psychology, and more). Each grad program has a unique combination of concentrations or tracks. As an example, Harvard University offers psychology PhD students a focus in one of four areas: experimental psychotherapy and clinical science; developmental psychology; social psychology; or cognitive, brain, and behavior. At Rutgers University, PsyD students can complete programs in clinical psychology, school psychology, or organizational psychology. At Columbia University, the MSW program has a variety of specific fields of practice for students to choose from, including aging; contemporary social issues; and family, youth, and children’s services. And Pepperdine University’s master’s degree in psychology focuses on marriage and family therapy.

The more clearly students have defined their interest area(s), the better you’ll be able to determine not only which degree makes the most sense for them but also, within that category, which specific programs will be the most fruitful match. These days, it is more effective to build an application list that fits an interest range than to apply to only PhD or only PsyD programs. If, like Thorn or Woods, students are specifically interested in a psychoanalytic lens, that will eliminate far more programs—and result in a list of much more appropriate matches—than choosing one degree type over the other right off the bat. Beltran was particularly drawn to Nova Southeastern’s wide variety of specialized tracks. “While choosing a concentration or track, students can see coursework specialized in certain topics,” she says. “In my case, I’m following the child and adolescent track, which so far has been giving me more in-depth knowledge through child-related courses.”

Identify Demographic Populations of Interest. Students may also have a preference for working with certain demographics, such as immigrants or the underserved. As Gayle describes, training at Nova Southeastern allows students to work with clients from across South Florida, the Caribbean, and elsewhere. “We are a destination state, so every kind of mental health condition you can think of, you’ll find it in South Florida,” he says. “If you can be trained in South Florida, you can work anywhere in this country.” For Beltran, the diverse demographics in the patient population was an important factor in choosing Nova Southeastern: “Coming from an Hispanic background, for me it’s very rewarding to work with the Hispanic population,” she says. “I want to be able to address the challenges that they have to help them improve their mental health and adjust to life in the US.”

Consider Personal Factors. Beyond the broad and granular outlines of the career students envision for themselves, there are personal factors and preferences to consider that will help them narrow down which schools to apply to and, ultimately, which program to choose. For example, consider geography: is your client committed to moving to or staying in a particular city—or, conversely, unwilling to move to a certain geographic area for school? (Thorn only applied to programs in the tri-state area because, by that point, she had a long-term partner and well-established life in New York.) What size program would help them thrive—a smaller program with more personalized attention or a larger program with more course options? And what are the student’s financial capacities?

The bottom line: spend a lot of time drilling down into students’ interests before you build a psychology graduate school list and prioritize the offerings of individual programs over the degree type. Take a cue from the experiences of Thorn and Woods and do not underestimate the role that emotion and passion should play in this decision. The specifics of what a program offers and requires, and the student’s gut-level pull toward that school, are far more important than the degree or the school’s ranking.

*Student names have been changed by the editor to maintain their privacy.

By Julie Raynor Gross, EdM, MBA, CEP, Collegiate Gateway LLC, IECA (NY)